Clips

BY LAUREN ROTH

THE VIRGINIAN-PILOT

MAY 14, 2008

VIRGINIA BEACH — On Saturday morning, 347 young black men have been invited to celebrate their academic prowess over sausage and eggs. All are graduating with at least a 3.0 grade-point average from a high school in Hampton Roads or the Eastern Shore.

The organizers of the breakfast wish there were hundreds more.

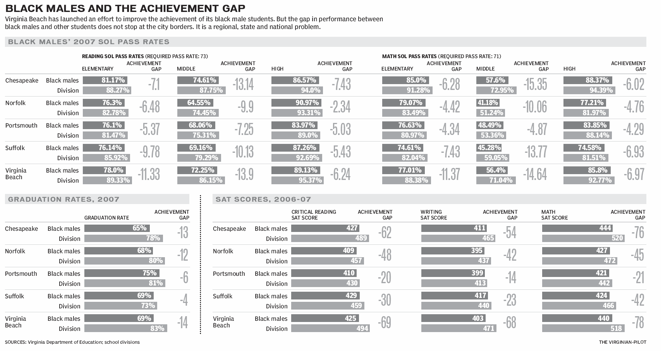

In each of the five cities of South Hampton Roads, black males graduate at lower rates, get lower SAT scores and fail state math and reading tests more often than their classmates.

Performance gaps between black and white students, with boys usually lagging behind, are pervasive.

“We’re very concerned,” said Bruce Hacker, education chairman for the Hampton Roads Committee of 200+ Men, the African American group organizing Saturday’s breakfast. “It’s an issue the entire region needs to be concerned about. It’s a nationwide crisis.”

In Virginia Beach, black males fall below city averages for graduation and college entrance test scores by the widest margins in South Hampton Roads. Beach educators have developed a plan to improve the academic results of those boys. It sets 12 objectives, including getting boys up to reading level by the end of third grade and cutting dropout rates by 25 percent.

At their retreat last summer, Virginia Beach’s School Board wrestled over choosing top academic priorities for the year. Ultimately, they picked improving academic results for African American males over greater parity among high schools.

“This piece gets them wherever they are,” be it elementary, middle or high school, board member Ed Fissinger said at the time. “We can come back and address the high school piece.”

Fellow board member Michael Stewart said the board chose the goal because “what is not a goal doesn’t get worked on.”

Experts say gaps by race and income are measurable when children enter school, and they can persist. Those differences were shrinking until the late 1970s, when schools stopped becoming more racially diverse, said Dan Losen, a senior associate with the Civil Rights Project at the University of California at Los Angeles.

According to a 2006 study by the Schott Foundation for Public Education, only 45 percent of black males graduate from high school, compared with 70 percent of the total student population.

Locally, the largest gaps between black males and their division graduation rate were 14 percentage points in Virginia Beach and 12 in Norfolk.

“We have a lot of people around here who are smart, but they don’t see us,” said Robert Isaac, a black 16-yearold who attends Tallwood High School and hangs out at a community center on Baker Road. “They don’t know what we can accomplish.”

When schools don’t reach black youngsters, results include high unemployment and imprisonment rates, a lack of access to college and unstable families, according to the Schott study.

The AVID program – Advancement Via Individual Determination – in Virginia Beach is helping students such as 18-year-old Joshua Bowens get invited to the scholars breakfast. Bowens said that before he enrolled in AVID, he thought going to college didn’t take any special preparation.

“I just thought you applied, you were in,” the Cox High School senior said.

AVID is aimed at middle and high school students who could succeed in college but aren’t on the right track. It is offered at middle and high schools in Virginia Beach and Chesapeake.

Bowens spent the past four years pushing himself to get better grades, taking challenging courses and preparing for the SAT, a test on which most black males score below average.

“Coming out of middle school, I was just reckless,” Bowens said. “Now I’ve got a 3.0.”

He plans to attend Christopher Newport University.

Nearly 80 points separate black males in Chesapeake and Virginia Beach from school division average scores on the math SATs. The gap is similar statewide. When compared to white males, Virginia’s black males were 92 points behind on the 800-point math test.

Black males fall behind for many reasons, said Madeline Hafner, executive director of the Minority Student Achievement Network, a national coalition working to close the achievement gap. They’re more likely to have less-experienced teachers, attend schools with fewer resources and take fewer upper-level classes, she said. They also are more likely to get in trouble or end up identified as learning-disabled or mentally retarded, according to the Schott Foundation study.

Comparable outcomes for black and white children are possible when they have quality teachers and take advanced courses, Hafner said.

“There’s a cultural mismatch,” she said. “Schools in the United States were developed for a certain type of kid – upper-class, white males who were going to go into law, medicine or religious training.”

That led to a certain type of instruction, she said: “Teacher talks, you listen.”

In Suffolk, principals and teachers are changing the philosophy of the classroom, said Deputy Superintendent Deran Whitney. For the past two years, teachers have been trained on how to reach different types of learners. Instead of writing a book report, for example, students might write a story, build a model, present a poster or craft a commercial about the book, Whitney said.

The schools with the best results teach each student in the ways they learn best, he said.

For the past three years in Norfolk, high school students have been organized into smaller groups and have shared a core curriculum that includes honors courses.

“We have high expectations for our students,” said Gene Jones, executive director for Norfolk’s public high schools. “Studies show students will rise to the occasion.”

Within five years, Norfolk officials hope fewer students will be held back and more will feel connected to the school, which can help reduce dropout rates. But Jones emphasized that their efforts are not aimed at black males alone. Blacks make up 63.9 percent of the student body in Norfolk.

“It’s for all children,” he said. “There is no target group.”

In Portsmouth, where 73.1 percent of the students are black and perform near division averages, officials also don’t target black males specifically.

In Virginia Beach, efforts are under way to start students on an advanced track earlier.

On state middle school math and reading tests, black males pass at rates 5 to 15 percentage points lower than their peers across South Hampton Roads.

During class visits in 2005, Mike Kelly noticed a pattern in the advanced sixth-grade classes at his school, Lynnhaven Middle. Few black children were in the seats.

Each year since then, Kelly, the principal, has visited or sent guidance counselors to elementary schools that feed into his school to ask them to recommend more capable black children for the higher-level math, science and English classes. Children who take them are more likely to take Advanced Placement and other upper-level courses in high school.

The effort has nearly tripled the percentage of African American students in advanced classes at Lynnhaven Middle, from 11.2 percent to 30.2 percent.

Larry Ames, principal at Seatack Elementary, takes the effort out of the school and into the homes.

“A lot of kids are getting lost,” he said.

Ames knocks on doors and talks to parents. He encourages them to emphasize the importance of education to their children.

Pastor Joe Flores, who runs the Newtown Cultural Life Center on Baker Road, said it is important to get the families involved.

“The community environment of the teenage boys I deal with on a day-to-day basis is not conducive to academic achievement,” he said. “It’s not enough to get it from school. You have to get it from home.”

But Flores feels the schools could work more with the community and direct more resources toward helping children in the critical preteen years.

Some steps are being taken. Among others, the Committee of 200+ Men is dispatching black men to mentor students in schools, churches and community centers in Virginia Beach, Chesapeake and elsewhere.

Jim Merrill, the superintendent of Virginia Beach schools, said change is beginning.

“I think we’ll keep getting better,” he said. “If someone says we’re OK, they need to go.”

“We have a lot of people around here who are smart, but they don’t see us. They don’t know what we can accomplish.” Robert Isaac, a black 16-year-old who attends Tallwood High School and hangs out at a community center on Baker Road.

Lauren Roth, (757) 222-5133, lauren.roth@pilotoline.com